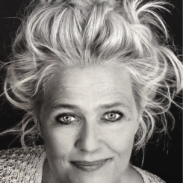

A portrait of sculptor Sigrún Ólafsdóttir – a conversation about her Icelandic roots, her work with wood, rubber and steel, and her current projects

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir (1963) studied sculpture in her hometown of Reykjavík, Iceland, and then continued her studies in fine arts and sculpture with Wolfgang Nestler at the Hochschule der Bildenden Künste Saar (University of Fine Arts) in Saarbrücken. The artist’s main means of expression are drawing and sculpture.

Her central theme is the relationship between two forces that condition each other, for example movement and rest, statics and dynamics, heaviness and lightness. In her sculptures, the material – steel, aluminium, latex rubber or wood – plays a central role.

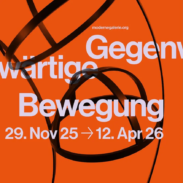

Her works are on display at the Galerie moderne in Saarbrücken as part of the exhibition “Gegenwärtige Bewegung ‘ (Contemporary Movement), which will run from 29 November 2025 to 12 April 2026. The artist, who has lived in Saarbrücken since the 1990s, was awarded the Albert Weisgerber Prize for Fine Arts by the city of St. Ingbert in 2022 for her outstanding work. For this special presentation in cooperation with the city of St. Ingbert, guest curator Andrea Fischer from the Albert Weisgerber Foundation selected works spanning several decades together with the artist.

Shownotes:

Foto Credits:

1: The portrait by Werner Richner

4: Dancer by Tom Gundelwein.

5: Duo: Erwin Altmeier

All others: Sigrún Ólafsdóttir

How to activate subtitles in your language

The video contains the original sound, so we have subtitled it for you.

- If no subtitles appear at all, move your mouse pointer into the video window on desktop/mobile computers or tap on the video on mobile devices

- Click on the square icon to the left of the cogwheel to toggle subtitles on/off.

- Normally, the language adapts automatically to your browser language settings.

- If not, you can choose your language by clicking on the cogwheel icon to the left of the YouTube logo.

Read our full interview with Sigrún Ólafsdóttir

Verena Feldbausch: Welcome to a new episode of art talk SaarLorLux, the podcast about art and creative people in our region. I am Verena Feldbausch and today I am particularly looking forward to talking to the sculptor Sigrún Ólafsdóttir.

Introduction to Sigrún Ólafsdóttir

Verena Feldbausch: Sigrún studied sculpture in her home town of Reikjavik in Iceland and continued her studies in fine art and sculpture with Wolfgang Nestler at the Saar University of Fine Arts in Saarbrücken. The artist’s main media are drawing and sculpture. Her central theme is the relationship between two interdependent forces, for example, movement and calm, static and dynamic, heaviness and lightness. The material, steel, aluminum, latex, rubber or wood, plays a central role in the sculptures. Today we talk about her artistic path, about sources of inspiration and what it means to live and work as a sculptor between two cultures.

Verena Feldbausch: Dear Sigrún, nice that we can meet in your studio today. If you had to describe yourself as an artist in a few words, how would you do it?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: It’s hard to say, because I’ve never done anything else. And that was always my niche as a child, where I had my peace and quiet and what I didn’t know, which back then meant meditation, being alone with God and the world. I used to do handicrafts and I never stopped.

Verena Feldbausch: Yes, that’s a nice statement.

Influence of Icelandic Origins

Verena Feldbausch: You grew up in Iceland, a country with a very special landscape and culture. How did this environment shape your artistic sensibility?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Well, there are people who say that my art is very Nordic. I don’t know what that means, because my art or my work is simply my work, what I have to do. And from inner movement comes an outer manifestation. But I think when you grow up with such extremes as in the north, we have an extreme amount of light and an extreme amount of darkness. And we also carry that within us. And I think that’s the main source.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: It was only later, and that’s the rewarding thing about getting older, to see, looking back, what it was that I was actually involved with. And that was always a struggle for balance.

Verena Feldbausch: Exactly, that’s actually your topic.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Yes, that is existential. It’s simple, why do I have to fight for every single piece of work so that it stands. Because I’m actually a very spontaneous person. I could also do – whoops – with big gestures. But I have always come back to balancing what I perceive in the world and what I perceive in my world.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: And then it was clear to me, yes, especially in this job, where I am now just the tool for what wants to be done. Yes, the best thing in life that I do. And also out of inner necessity. It was simply a lifesaver for me as a child, for example. While for others it was books or sport. I also did sport, which was also very, very good for me. But that was simply what helped me on the way to finding this balance point. That’s why I’ve often said when people say, what do you do for a living? I am a tightrope walker.

Verena Feldbausch: Beautiful picture, yes. It’s about balance, exactly.

Path to Sculpture

Verena Feldbausch: What originally led you to sculpture? Was there a moment when you knew that “this was my medium, that I wanted to get to grips with it”?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: That was the three-dimensionality. I also drew houses, rooms, all sorts of things, before I started sketching with material. I was lucky, in a town, which was a village in Iceland at the time, we could get endless amounts of leftover material from the workshops. Wood, there was also a rubber workshop and a leather workshop. That simply attracted me more, something plastic from all sides. Of course I also drew a lot, but that was the fascination of versatility in the truest sense of the word. A subject always has several sides, not just one. Below, above, all sides, that was the big attraction.

Life and Work in Saarbrücken

Verena Feldbausch: You now live and work in Saarbrücken. What brought you here and how does living here influence your work?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: I originally came to stay for just three or four years.

Verena Feldbausch: To study?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Yes, to study. Simply because I had the opportunity, because you couldn’t do a degree in Iceland back then and I wanted to take the opportunity to go abroad. And the reason why I chose Saarbrücken was that we always had visiting professors in the sculpture department in Iceland and they were from Germany. And one of them, Volker Nestler, got a professorship here, i.e. a position at the HBK, and told us that if we wanted to go abroad, we should take a look at it. Because it wouldn’t necessarily be better to be in the big cities. And the main reason was that my son was two years old at the time and I knew it was easier to be alone with a child in a smaller community than in a big city. And that was the reason why I looked at it here and I thought it was good, clear and I decided to study here and do my diploma.

Verena Feldbausch: It wasn’t possible for you to do a diploma in Iceland back then?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: No, that was a master. You could do an intermediate or bachelor diploma. Similar to BAföG, you get student loans in Iceland if you can’t finish your studies in Iceland.

Verena Feldbausch: Ah yes. Okay, that’s interesting, yes.

Work Process and Material Choices

Verena Feldbausch: The preparation of a sculpture is time-consuming. How long does this preparation process take? How do you proceed artistically? Do you make preliminary drawings? I know that you build models. How does that happen?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: It usually starts as a rough sketch on a piece of paper. Then I start sketching directly in the material to at least rule out what doesn’t work. And then develop it step by step. It often starts with a lot and then it’s about getting to the point and removing everything that isn’t necessary.

Verena Feldbausch: Can you say how long such a work process takes?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Very different. I have received perhaps two works as gifts in my life that have slipped out of my hand. But the rest is all wrestling. Some are also here and are not finished. But sometimes they look at me, after five years, and I know that’s the final part. Now I know how it has to be done.

Verena Feldbausch: That’s great.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Yes. It is different. Of course, it’s quite different when I make works for outdoors. For example, this art in construction in Iceland. It must be earthquake-proof. It has to withstand wind. And then there is the work with a structural engineer. I’ve been doing the same thing for over 30 years.

Verena Feldbausch: Exactly. That brings us to materiality. So your works are made of steel, aluminum, latex, rubber or wood. How do you decide which material suits an idea?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: That depends on the work itself. So of course I’m a materialist because I work with materials. But the material itself, as with stone sculptors or steel sculptors, was never my medium, but simply the material that springs from the idea. For example, if I want to make something fragile, then I make it out of my wood. Because it looks like it’s more fragile, even though it’s not. This means that the idea looks for the material it needs to unfold.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Just like this one, where I started with the rubber, this series of works, the relaxation or expansion with the solid core and the liquid… Then I thought, what can support this idea?

Verena Feldbausch: And here’s one more thing. As with every podcast, we post pictures of the work discussed on our blog. And you can find out how to get to the blog in the show notes. And now back to the podcast.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: And then I came back, also to my childhood, where we had rubber, and thought, yes, that would be exciting. Simply the haptic. This also has something almost like human skin. That is also exciting. This is often the case in exhibitions, where the guardians of the exhibition say, people want to touch it. And that invites you to do so. I find that exciting. Just like human skin.

Verena Feldbausch: But I also have this impulse very often when I go to an exhibition of sculptures, that I want to touch them. Well, but that’s not always allowed.

Physicality in Sculpture

Verena Feldbausch: Sculpting is also very physically demanding. What role does the physical aspect play for you in the creative process?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: At the moment, where I am now, I can of course only build models, something physically light. But I used to do very hard physical work. But now the industry is doing it. So I work with a good locksmith and he then takes over the execution in either aluminum, steel. Then I supply the drawings and models, which are then checked by the structural engineer.

Verena Feldbausch: And the models are usually made of wood, aren’t they?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: I usually make my models out of wood. I’ve had my favorite material from the very beginning. This is the aircraft plywood from Finland, birch, which used to build gliders. A great material.

Verena Feldbausch: The models I see here are often black. Do you paint them then?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Exactly. As I said, my works don’t need any color. And yet they contain all the colors. Because between the white in the light, light is white, and the black are all colors. So the viewer can choose its own color.

Verena Feldbausch: Yes, that’s the whole spectrum of colors.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: The whole spectrum.

Verena Feldbausch: Between black and white.

Significant Works and Inspiration

Verena Feldbausch: Is there one work, or perhaps several, that you have grown particularly fond of? Perhaps because it challenged you technically or emotionally?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: I don’t know. This is a continuous process. That’s just how it grew. Sometimes I also fall back on old ideas that I didn’t appreciate at the time, that have grown with current experience. And this combination is interesting. Because I think that even if we are lucky enough to live to be 100 years old, that’s why I say that no work is old. And what is my life’s work? What is a new work? It comes from experience. And this activity is like research. This curiosity and eternal research. Try it out again and again. Never stop being curious.

Verena Feldbausch: That’s also a nice motto for life.

Verena Feldbausch: Let’s move on to the topics and inspiration. So your sculptures are about opposites. About black and white, male and female, hard and soft, distance and closeness. What interests you about these contrasts?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: My inner balance point. I know that now.

Verena Feldbausch: You know it after years of research.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: I didn’t know it 30 years ago. Why have I been doing this all this time? And just like that.

Verena Feldbausch: And how do you find the balance between these opposites?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: By doing that. Like a meditation, not just sitting down twice a day, but the whole day. It’s a bit like how musicians have to sit and practise notes in order to be able to play the greatest works. It’s about simply trying, trying, trying. Throw it away, keep trying, practise. Until that is true at some point. And that is what I mean by this meditation. Pausing, despite all the opportunities to throw things against the wall and say how I used to do it. I am untalented. Why did I study art for eight years? If nothing comes of it. And that’s the difference now. And simply with more patience and understanding for the whole thing. It’s simply practicing, perseverance, determination. And if something is wrong and starts to annoy me, to sit down and say, okay, now it’s time to go home and I’ll look at it tomorrow. Is it really as bad as I think it is now? That is the difference.

Verena Feldbausch: That you no longer throw everything against the wall, but simply say, okay. Perhaps a break is called for.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Exactly.

Dynamics and Movement in Sculptures

Verena Feldbausch: And your sculptures are often not static, but in motion. Take the dancer, for example. This sculpture moves, it is dynamic. Why is this important to you?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Because without movement, life and everything stagnates. Not all my works are like this, but now we’re talking about the dancer. I also see them as bodies. I’ve always been so one-to-one, me and my counterpart, who is also something human, is perhaps too much to say, but it’s also an individual. That’s why I was never in favor of pedestals. If possible, I was in favor of something that could stand on its own on the floor without needing help. And at some point it came to the dancer. And I knew that it needed a very light side and a very heavy side. And that had to be brought into balance. Both with the height and shape of the wing and this hemispherical segment, which has to be stable enough, yet light enough to turn in the wind.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: And I spoke to my structural engineer about how I could do this. And then he said, I can’t do that. Because I have to have a fixed shape. A fixed point. So then, as I said, the eternal experiment started again. And that’s the case with – I’ve done different types of dancers – and everyone is only made for itself. I can’t make it twice. And the way the weights and how this hemispherical shell is plumbed is a unique thing. Where it has to be constantly tried. With the movement of the wing, with the inclination of the wing. In combination with the diameter shown below. And that it can still move. And that simply is… it’s very human. It is easy to fall despite all the possibilities. It is actually a miracle that we are alive. How often have we had the opportunity to simply fall once and for all and not get up again? And they are all balanced in such a way that they can be used even at the highest, not the end of the world, of course, but in the strongest winds they are balanced so that they don’t fly away.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: But the exciting thing is, in the past, they didn’t used to have this turntable with ball bearings to keep them in one place. Because if they didn’t have that, that support with ball bearings, that it can move, then they wandered in the wind. And of course that wasn’t good when they wander across the street and somehow walk into the city. In other words, the idea has evolved so that they simply stay in place, but can still turn and move.

Verena Feldbausch: Yes. Exactly.

Verena Feldbausch: And as we have already said, your work is often about the brief moment, when both opposites are equally strong. So when they are in balance. I quote Cornelieke Laagerwart: It is about the pause between inhaling and exhaling, between ebb and flow, between centrifugal force and gravitational pull. When the ball thrown up hangs in the air for a moment. What do you think of this moment?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: He’ll come to me when I’m ready. And I often have to wait a long time for it. I can’t force it.

Verena Feldbausch: That’s what you said about putting the work away, putting it away again and then looking at it again. And then it can take years.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: I think that’s what most artists do. For this, we can call it a reward, but you struggle for so long, you are sitting for so long, practicing, practicing notes. Like the musicians, they have to sit for a long time. Then suddenly this happens. And that’s the moment when I say it’s not me doing it, it’s happening. Where you are simply the tool that is ready to happen.

Verena Feldbausch: To allow that to happen.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Allowing and being open to it. It’s also about being open to this moment. And I can’t force this moment. That is the be-all and end-all. I think that’s where I realized pretty early on that I couldn’t imagine doing anything else. To experience such moments when everything is right and everything falls into balance. The other is practice, of course. It often starts very easily with an idea. Then comes the process and you think, what is this actually? And then simply, as I said, this patience, this understanding for what wants to be born, not to give up.

Influence of Icelandic Culture

Verena Feldbausch: Does your Icelandic origin also play a role in the content of your sculptures? So I think of the myths of nature spirits, of elves and trolls, of symbols and of the very special landscape in Iceland.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: For sure. So these extremes alone. They are simply crazy people. With crazy natural elements. Light, dark, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions. We become all the more aware of the fact that we only have a very thin crust like an apple skin, when you have a huge apple, then everything inside is a glowing core. And it only takes one tiny little accident to wipe it all away. Because you can experience it with us. And I also grew up in a place like that in Iceland, where you either saw earthquakes in waves and thought you were suddenly on the sea in the meadow, or you were looking out of the kitchen window at a spewing volcano. For us, this is natural because we don’t know anything else. We also have this respect for these forces of nature. And it certainly has something to do with these opposites and the light and dark sides of me.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: I now think and feel that it’s the DNA of Icelanders and everyone who lives this far north.

Approach to Death and Spirituality

Verena Feldbausch: Is there a different way of dealing with death in Iceland?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: You know, it’s like that. We actually have the best of both worlds through paganism and Christianity. When they were on the road, the Christians. Then our pagan chieftain sat under the fur day and night. And said to his people: we accept Christianity. Otherwise they will slaughter us all. But they only come twice a year to check us out. And we have the best of both worlds.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Every grandpa goes with a child, even if he says, what kind of superstition is that, there are no elves and trolls, and tells the grandchild that. I say my grandpa was my everything. I was lucky. My parents were so young, they were 20 and 23 and didn’t even know each other when I was conceived. My mother somehow thought it was time to try having sex because her friends had all done it. And she got pregnant the first time. She hadn’t thought of that. And they didn’t know each other, my parents. And yes, you simply live with it differently. That’s how it is … we are also sometimes envied. I also say, you know, the ones who left like my grandpa. He was my surrogate father. I was the first grandchild and born on his birthday. And he waited a long time for it, because my grandma and grandpa had lost their first three children at birth.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: And my mother and my aunt lived. In other words, he loved children and waited for children. And the relationship between my parents was very difficult. And I always had my niche with grandma and grandpa. And I thought God was going to die when I was 14 and my grandpa was dying. And then he said, Sigrún, you know I’ll never leave you. Even if you don’t see me anymore. I will always be with you. And all you have to do is call me and I’ll come. And I swear to you.

Verena Feldbausch: Yes, fine.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: And that has always been the case. We are not in God’s fear or God’s dread. We are believers, but not religious. That is the difference. We believe, but it is not the punishing God. We always go to church at Christmas and so on, because it is simply for the beautiful music. The pastors also keep it short, because they know people come for the beautiful Christmas music and for the whole… For the atmosphere like this. Yes, and my great-grandfather was the most famous pastor, that existed in Iceland. Several volumes have been written about him. Because he was a social worker. He had eleven children himself. They all lived. There were many child deaths. He rode from farm to farm. He was in the country to simply teach people about cleanliness. And you know, the human thing. And even if he was in the country and the farmers came to church on Sundays, then he also kept the sermons short, because people had come to sniff and kiss. And you know, the younger people preferred hand in hand and have a little snog somewhere in the meadow. You know, it was about humanity.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: And that, I think, is the difference. So we have the most beautiful of paganism and Christianity. And Siggi, my son, he also lost his father at 49. And he said that Dad is with me every day when I need advice. He was also an artist, a musician. And you know, in his subject now at Kulturgut Ost, he needs advice. Dad, how would you do it? And then the Germans sometimes say, you know, are you Icelanders all crazy? No. I say, you know, the ones that go away, they haven’t gone any further than that, that every day they are with us. But we don’t go to cemeteries, they’re not there. Well. They are in us, with us.

Emptiness and Space in Sculpture

Verena Feldbausch: How do you deal with the topic of emptiness and space? So in sculpture, it is what is not there, often just as important as what is there.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Exactly, it’s like those pauses between breaths. It also has something to do with that. And I see my work… most of my sculptures are, I also see them like drawings. And it’s important to me that you can go in and out. It was also important to me, for example when working in the city, Duo, at the same time, because it was supposed to, even if it didn’t turn out that way, it was supposed to be a square, which it didn’t become, because we got other information about the place.

Verena Feldbausch: This is the place where your sculpture now stands here in Saarbrücken.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Yes, near the Café Bar Celona.

Verena Feldbausch: Exactly, on the Saar.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Yes. And there was meant to be more space. And they now have more seating than we were told. It was important to me to do something that children could get in and out of, where it is also a place where you can play. And that’s the thing I’m most happy about, where I go to visit it from time to time, the children hang on the rubber, they climb and the skaters also ride there. You can see in a few places in the sculpture where it is very smooth, and that’s where the skaters tried to go, to integrate this into society, to bring it to the people. That it is not just somehow a sacred statue, but, and that’s what I’ve tried to do now in the sculptures that are outside, that you can go in and out.

Verena Feldbausch: And that the material can withstand it.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Yes. As fragile as possible. And again, standing, despite the possibility of falling.

Stability and Instability

Verena Feldbausch: Yes, exactly. And that’s what’s so interesting about your sculptures. They are elegant and at the same time you have a sense of threat. So you ask yourself, how does it actually hold what is hanging from the ceiling or swinging outside? Doesn’t that somehow fall over? So can you tell us something more about the relationship between stability and instability?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: That brings me back to myself. It’s just like inside us. Sometimes the anger glows and sometimes there is stoic calm. And that is also in the works. Without intending to do so.

Verena Feldbausch: I think your sculptures are often super elegant. You have such beautiful sculptures, the ones hanging from the ceiling for example. Or when I’m standing next to the dancer, I ask myself, isn’t he going to fall on me or something? There is a kind of threat, that is perhaps too much to say, rather a fear for this balance?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: That’s the part that’s intentional. This is about mindfulness. A lot of my work, if you’re not careful with it, you can hurt yourself. Just like with everything else. But that is intentional. Mindfulness has never been as necessary as it is now. Because it is carelessness and ignorance that has simply brought us into the world where we are now. Indifference. This lack of feeling for togetherness, for each other, cohesion. But in the case you asked, no, it doesn’t fall over because it has been tested several times and is not a coincidence. Instead, what seems threatening is stable in itself, even if it appears so.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: It is a reminder of what can happen. And that, in turn, is also these two sides of me that I know very well. Because I know my bright side, I also know my dark side. They are dark. And just as it is important for me to get this right, the same rules apply to my work. And that is again, from the inner strength comes the outer appearance.

Artistic Influences

Verena Feldbausch: Are there any artists who have particularly influenced or accompanied you?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: I have several favorites. Louise Bourgeois was always one. Eva Hesse. I could name many. There were also British artists in the 80s, such as Richard Deacon, Tony Cragg and then (Barry) Flanagan and several others. I saw an incredibly beautiful exhibition in San Francisco. That was in ’87, because I know I was heavily pregnant at the time and wanted to take the opportunity before a child came along and took some time. Yes, even the things by Goya in the Prado, for example. I could go on for hours… That is simply across history. Yes, and you just get influences anyway, because it’s so much. And in most artists, this influence or experience is in some way reinterpreted or recaptured and brought into the world.

Verena Feldbausch: Exactly, and that’s the interesting thing about art.

Art Scene in SaarLorLux

Verena Feldbausch: How do you experience the art scene in our region, i.e. SaarLorLux, especially for female sculptors?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: This is rare.

Verena Feldbausch: Yes, I also have to think about which female sculptors there are in the area.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Me too. There are some who do both, so they’re into this, how do you say, sound art or something, but that’s not much. Yes, as with competitions, I’m often the only woman there. Or maybe two, three and seven men… yes, that’s what it says.

Verena Feldbausch: Yes, the art scene is not so open to female sculptors now, or what is the reason for that?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: It’s more time-consuming, you need more space, it’s heavy, it’s incredibly impractical. What have I done here? As my son said when he helped me here with the last move. Mom, why didn’t you choose something practical, like becoming a librarian? Dear, I have no sense of humor about it now. Yes, yes. No, it’s clear, it’s much easier with two-dimensional. To store that too.

Verena Feldbausch: That’s right, yes.

Two-Dimensional Works

Verena Feldbausch: Exactly, and here we still come to your two-dimensional works. We haven’t even talked about that yet, about the drawings and paintings. I think, as I said, the sculptures are often very, very delicate. And I’ve seen black tubes in the drawings. And yes, they are actually quite massive. How do you develop your drawings?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: I needed time to appreciate my drawings. It was often such a welcome break to simply do something on canvas. So I’ve always drawn on paper, but at some point, as I tend to do big things. Of course, this touches between painting and drawing. But where it was just too big to frame or find paper when it goes the dimensions of two to three meters or larger, then I made my own ground, similar to handmade paper with a chalk base. And consciously too, when I was there with big gestures and black and then white, just in front of me, to work spontaneously. And I said, yes, that also offers the reverse, that a drawing can be heavy and massive, even if it has a certain movement and lightness to it, in contrast to sculpture, where it was always actually the opposite pole. So sculptures were heavy and drawings were light.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: And of course I also made very simple, light drawings, but these were often also the preliminary stage of movements in my sculptures. And then the others, for example, these ink and gesso drawings, almost like watercolors, several layers on top of each other, about this transparency. Then I was more interested in the movement.

Verena Feldbausch: You are also showing a fairly large drawing in your exhibition in the modern gallery.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: This is also a large ink and gesso drawing. So two, respectively. One format is 160 or 180 by three meters, and one 140 x 140. Of course we chose it together, me and the curator.

Public Projects and Exhibitions

Verena Feldbausch: You won the first prize in a competition in Raikjavik to design a public square. This is where the sculpture Reziprok, made of Corten steel, will go. And you are in the process of carrying out this order, so to speak. Yes, how far along are you? So what is the current state of affairs?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: We are so far along that all we really need is a fixed date in Iceland when it will be set up. It’s difficult in winter, little light, snowstorms. But soon we will start building here. It’s being built here, by my locksmith. Transported over it. And then he also comes along and sets it up. And I reckoned we wanted to have it ready by the end of the summer, but there were a few things in the contract that we had to work on in more detail. Purely practical things and that’s how I estimate it will be set up in Iceland in the spring.

Verena Feldbausch: And where exactly does it go?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: It is in the center of Reykjavik in a new building complex. There is an inner courtyard that is still open, but there is a place for a market and coffee, hotels, all kinds of activities, where several thousand people pass through every day. And within this building complex, which is open and accessible to all people, that’s where it comes in.

Verena Feldbausch: Yes, fine. Great place, for sure. And very complex. So it is, in terms of dimensions, how big is it?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: 10, 12 meters wide, 10, 12 meters high. In this dimension. Oh, yeah. A grand gesture.

Verena Feldbausch: That means it will probably be inaugurated sometime next year.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: We’re actually just waiting for news from Iceland, because they’re organizing it locally with the cranes and all the housing we need for welding and everything. Because this is of course a huge building.

Verena Feldbausch: Yes, yes.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: I have been working with a locksmith for over 30 years. We know each other very well by now. It is very valuable. He knows my way and I know his. And this has naturally grown together and matured during this time.

Verena Feldbausch: Lovely… I wish you every success.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Thank you.

Verena Feldbausch: Yes, I’m very curious.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Me too.

Albert Weisgerber Prize and Exhibition

Verena Feldbausch: Let’s move on to the Albert Weisgerber Prize 2023. You won that one. Congratulations to this award.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Thank you.

Verena Feldbausch: And to mark the occasion, your works will be on display in a solo exhibition at the Moderne Galerie in Saarbrücken from November 29. What message or emotion do you want visitors to experience when they stand in front of your sculptures or drawings?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Touch. That’s what I always wish for when I go to exhibitions or when I go somewhere, no matter what it is, whether I’m going to the opera or something, it’s to be touched by something.

Verena Feldbausch: It’s important that art touches you.

Verena Feldbausch: The exhibition is entitled Contemporary Movement. Does the title also allude to today’s political and social movement?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: In a certain way. I had a different title in mind, but we had also talked about it for a long time, the curators and I, that might be too much to say. But that my works are actually always about movement. Movement, agility, progress, development, no stagnating. Then we both found that this was suitable for both my works and, of course, the present. Very fitting.

Future Perspectives and New Materials

Verena Feldbausch: Is there any other material, for example, that you would like to try out?

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Yes. There are industrial materials that I haven’t tried yet, because I’m also interested in the development of materials in research. What is on the tip of my tongue, but is not yet concrete. If possible, something environmentally friendly and maybe it will look in the end like something in complete resolution or release…. in that direction, that would be nice. Like a cloud that disperses. But I haven’t tried it yet, but I already have an idea of new experiments through curiosity.

Verena Feldbausch: Very nice. We are very excited and are waiting to see what else you show us.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Yes, I’m curious about that too, because I never know. And that is perhaps the most exciting part of the whole thing.

Conclusion and Outlook

Verena Feldbausch: Thank you, dear Sigrún, for this inspiring conversation and for the insights into your work.

Sigrún Ólafsdóttir: Thank you very much, dear Verena.

Verena Feldbausch: If you are now curious and would like to see Sigrún Ólafsdóttir’s sculptures here, can find information about current exhibitions and works in public space in the show notes. That was art talk SaarLorLux, the podcast about art and creative people in our region. I am Verena Feldbausch and thank you for listening and I am already looking forward to the next episode of art talk SaarLorLux. See you then. Did you like art talk? Then leave five stars and recommend us to your friends. You can find more information about the podcast in the show notes and in our blog. Be there again when it says we talk about art at art talk, the art podcast from SaarLorLux.